The Platform Workers Act 2024 in Singapore: Pioneering Regulation for the Gig Economy

The gig economy has transformed the labour landscape. With digital platforms like Grab, Foodpanda and Deliveroo, platform work has become an integral part of the economy. These platforms rely on gig workers to provide essential services, such as food delivery and ride-hailing, offering flexible income opportunities. However, this flexibility has often come at a cost: limited worker protections, inconsistent incomes, and a lack of access to social safety nets.

Recognising these challenges, the Platform Workers Act was introduced in 2024. This landmark legislation aims to ensure that workers receive better protection while maintaining the economic viability of platform work. This article explores the key provisions, implications, and its significance in shaping labour future.

- The Rise of the Gig Economy in Singapore

Over the past decade, the gig economy in Singapore has grown. Fueled by technological advancements, platforms like Grab and Deliveroo have created opportunities for individuals seeking flexible work arrangements. As of 2023, it is estimated that over 70,500 platform workers operate in Singapore. This makes up approximately three per cent of the workforce. Of these, 33,600 were ride hailing drivers, 22,200 were cab drivers and 14,700 were delivery workers.[1].

In 2023, Singapore’s Ministry of Manpower (“MOM”) announced the creation of the Platform Workers Work Injury Compensation Implementation Network (“PWIN”)[2]. This initiative focuses on formulating policies and operational details to implement a comprehensive work injury compensation framework for platform workers. To elaborate, the PWIN involves collaboration among various stakeholders, including platform companies, insurers, and tripartite partners. Thirteen platform companies were listed as participants in this initiative: (i) Ride-Hailing Platforms: Grab, Gojek, Tada, and Ryde; Taxi Operator: ComfortDelGro, which operates the Zig ride-hailing app; (iii) Food Delivery Platforms: Deliveroo and foodpanda; (iv) E-Commerce Platform: Amazon and Parcel Delivery Services: GoGoX, Lalamove, Pickupp, uParcel, and Teleport (the logistics arm of AirAsia)[3].

Despite its growth, the gig economy has faced criticism.

Firstly, it has been recognised that platform workers, classified as independent contractors, do not receive Central Provident Fund (“CPF”) contributions, leaving them without adequate savings for housing or retirement. This is coupled wit the fact that they face income instability due to the highly fluctuating demand and service disruptions. Hence, this puts them in a precarious position in terms of housing and retirement, which can contribute to a wider social issue.

Next, these platform workers are often delivery workers and are arguably more exposed towards traffic incidents. Hence, workers injured during their duties often struggle to secure compensation or medical support.

The growing prevalence of these challenges, together with the exponential rise in platform workers spurred calls for reform.

- Key Provisions of the Platform Workers Act 2024

The Platform Workers Act was passed in 2024. It aims to address the unique vulnerabilities faced by gig workers while maintaining the flexibility and innovation of the platform economy. Its approach is four -pronged.

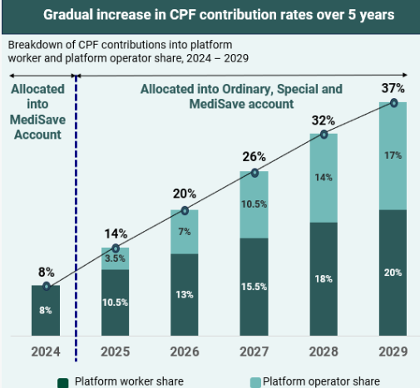

Firstly, it aims to enhance financial security by mandating CPF contributions for platform workers. Younger workers who are born on or after 1 January 1995 will automatically receive CPF contributions. Meanwhile, older Workers may opt-in. In essence, workers born before 1 January 1995 can voluntarily participate. Both the platform workers and platform operators will contribute CPF which will gradually increase over 5 years to align with those of employees and employers, reaching up to 20% (platform worker’s share) and 17% (platform operator’s share) by 2029, enhancing workers’ housing and retirement savings[4]. This is illustrated below[5].

Next, it seeks to provide work injury protection under the Work Injury Compensation Act 2019 (“WICA”), aiming to ensure a standardised injury compensation framework[6]. To elaborate, platform workers will enjoy the same coverage of benefits under the WICA as employees including: (i) medical expenses, (ii) lost wages and (iii) compensation for permanent incapacity or death.

The steps to determine work injury compensation for platform workers are as follows[7]:

Step 1: Calculate Average Daily Earnings (“ADE”)

(i) Identify Gross Earnings Across Platforms

Calculate the platform worker’s total gross income from platform operators within the service area where the injury occurred. This involves reviewing the worker’s earnings over a period of up to 90 calendar days before the date of the accident.

(ii) Define the Lookback Period

The 90-day lookback period starts from the day before the accident (Day 1) and works backward. For example, if the incident happened on 10 April 2024, the lookback period begins on 9 April 2024 and ends on 10 January 2024. If the worker started platform work less than 90 days before the accident, the lookback period is shortened to match their actual working days.

(iii) Compute Total Earnings Per Day:

Divide the total earnings during the lookback period by the number of days in that period.

(iv) Apply Fixed Expense Deduction:

Deduct a fixed percentage, which varies depending on the mode of transport used:

- 60% for cars, vans, lorries, and trucks

- 35% for motorcycles and power-assisted bicycles

- 20% for bicycles, walking, or public transport.

(v) Final Calculation

ADE = Total earnings per day x (100% – Fixed Expense Deduction Amount)

Step 2: Apply the formula below

Compensation for medical leave

Compensation for hospitalisation leave

- Implications of the Platform Workers Act 2024

The introduction of the Platform Workers Act 2024 provides enhanced financial security to platform workers in that the CPF contributions significantly improve workers’ ability to save for housing and retirement. Furthermore, work injury compensation ensures financial support in case of accidents, leading to an enhanced safety net.

Meanwhile, in connection with the impact it has on platform operators, higher operating costs in the form of CPF contributions and insurance premiums will increase operational expenses. In addition, platform operators may need to adjust its business model to accommodate the increase in pricing, commission rates or worker incentives.

Lastly, this additional costs borne by platform operators may be passed on to customers in the form of higher service fees. Nevertheless, this article is of the view that given that businesses operate under the forces of supply and demand, consumers and service providers should be given the freedom to make decisions that align with their preferences and needs. If new regulations increase costs for platform operators, higher fees simply represent the true cost of ethical and sustainable operations. Consumers who truly value fairness and worker welfare may accept or even support paying slightly higher fees as a trade-off for ensuring better conditions for platform workers.

- Challenges

This article acknowledges that there are some problems which have remained unsolved or create new difficulties.

Firstly, CPF contributions reduce immediate earnings, especially for platform workers who rely on gig work as their primary income source. This can significantly reduce their disposable income. For example, a food delivery rider earning $2,000 monthly may now see a portion of their income deducted for CPF contributions, leaving them with less cash for daily expenses. While CPF ensures long-term financial security, the immediate impact may deter some individuals from continuing gig work. This may lead to a labour shortage.

Next, the new regulations may pose monitoring and enforcement challenges in ensuring that all platform operators comply with the law and that workers receive their entitled benefits requires robust monitoring and enforcement mechanisms. For example, a parcel delivery platform might underreport earnings or fail to provide work injury compensation, exploiting gaps in enforcement. To address this, the government must allocate resources to conduct audits and address non-compliance, which could strain regulatory capacity.

- Conclusion

To conclude, the Platform Workers Act 2024 represents a significant step forward in addressing the systemic inequities faced by gig workers in Singapore. By mandating CPF contributions, ensuring work injury protection, and empowering workers with collective representation rights, the Act seeks to strike a balance between worker welfare and industry sustainability. While challenges remain, the legislation sets a strong foundation for a fairer and more resilient gig economy.

This article was authored by our Founding Partner Oon Thian Seng and Senior Associate Angeline Woo.

Oon & Bazul LLP’s Employment Practice encompasses both contentious and non-contentious employment matters across various industries. Clients include banks, financial institutions, multinational corporations, insurance companies and governmental bodies as well as senior management, executives and professionals.

We believe that it is important to engage our clients’ human resource managers when tailoring employment contracts and policies for our clients. We ensure that our clients’ employment policies are not only practical and compatible with their existing organizational structure but are also capable of preventing unnecessary disputes with or among employees.

You may visit our Employment Practice page to learn more about our practice. You may download a PDF Copy of the article here.

[1] https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/politics/what-you-need-to-know-about-the-new-platform-workers-bill

[2] https://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroom/press-releases/2023/0203-formation-of-pwin

[3] https://www.mom.gov.sg/newsroom/press-releases/2023/0203-formation-of-pwin

[4] https://www.cpf.gov.sg/member/growing-your-savings/cpf-contributions/saving-as-a-platform-worker

[5] https://www.cpf.gov.sg/member/growing-your-savings/cpf-contributions/saving-as-a-platform-worker/born-in-1995-or-later

[6] https://www.mom.gov.sg/employment-practices/platform-workers-act/work-injury-compensation-for-platform-workers

[7] https://www.mom.gov.sg/employment-practices/platform-workers-act/work-injury-compensation-for-platform-workers